-

- The collapse began on Black Thursday, October 24, 1929.

Trading opened with a wave of sell orders that overwhelmed the exchange. Stabilizing bids briefly slowed the fall, but confidence was already damaged and selling pressure continued into the following week. - Across the four main days, the Dow fell roughly 25 percent.

About 30 billion dollars in paper wealth vanished in late October alone. In today’s terms that is hundreds of billions of dollars, a shock that hit households, banks, and businesses at the same time. - Black Monday and Black Tuesday, October 28 and 29, set volume records.

Daily turnover surged into the tens of millions of shares, several times the normal pace, as investors rushed to exit. Ticker machines lagged hours behind, leaving traders flying blind while prices kept sliding. - Speculation had been building for years.

From 1922 through 1929, stocks rose steeply and margin debt ballooned. Popular favorites like radio and utility companies traded at lofty valuations that assumed uninterrupted growth. - Buying on margin magnified losses.

Investors often put down about 10 percent and borrowed the rest. When prices fell, brokers issued margin calls that forced sales into a falling market and accelerated the decline.

- The collapse began on Black Thursday, October 24, 1929.

-

- Banks and their securities affiliates were underregulated.

Some institutions used depositor funds indirectly for stock speculation or sold risky securities to retail customers. When asset prices fell, losses flowed back to the banking system. - Thousands of banks failed between 1930 and 1933.

A series of banking panics followed the crash as depositors lined up to withdraw cash. With thin reserves and falling collateral values, many banks could not meet withdrawals and closed. - Myths grew in the retelling, including stories of mass suicides.

While the era was traumatic, contemporary records do not support claims of a widespread wave of such incidents on Wall Street immediately after the crash. - Policy mistakes made the downturn worse.

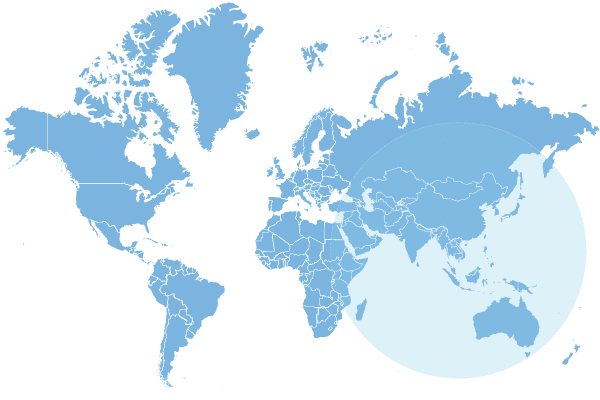

The Federal Reserve had tightened credit into 1929, then struggled to arrest the collapse as banks failed. Fiscal policy remained constrained early on, limiting support for demand. - Trade barriers deepened the global slump.

After the crash, tariffs such as Smoot Hawley reduced international trade as other countries retaliated. With the world still on the gold standard, credit conditions tightened across borders. - The Great Depression lasted roughly a decade.

Industrial production fell sharply, unemployment in the United States peaked near one in four workers, and deflation raised the real burden of debt for businesses and homeowners. - By 1933 the market had lost almost 90 percent from its peak.

Household incomes dropped by more than 40 percent and many families relied on public relief or informal support networks to get by.

- Banks and their securities affiliates were underregulated.

- Reforms rewired American finance.

The Glass Steagall Act of 1933 separated commercial banking from investment banking and created federal deposit insurance through the FDIC. The Securities and Exchange Commission followed in 1934 to regulate markets and disclosures. - The Dow did not regain its 1929 peak until November 1954.

Investors who bought at the top faced a 25 year nominal recovery period. Diversification, valuation discipline, and prudent use of leverage became enduring lessons for later generations. - Key takeaway for today.

Booms built on leverage are fragile. Transparent information, adequate capital, liquidity backstops, and sensible risk controls help prevent a market break from turning into a full economic calamity.

Have another fact about the 1929 crash that readers should know? Share it with us and help keep history accurate.